Remembering Ron Miller: How His Actions Shaped The Future of Disney

By Matthew Anscher

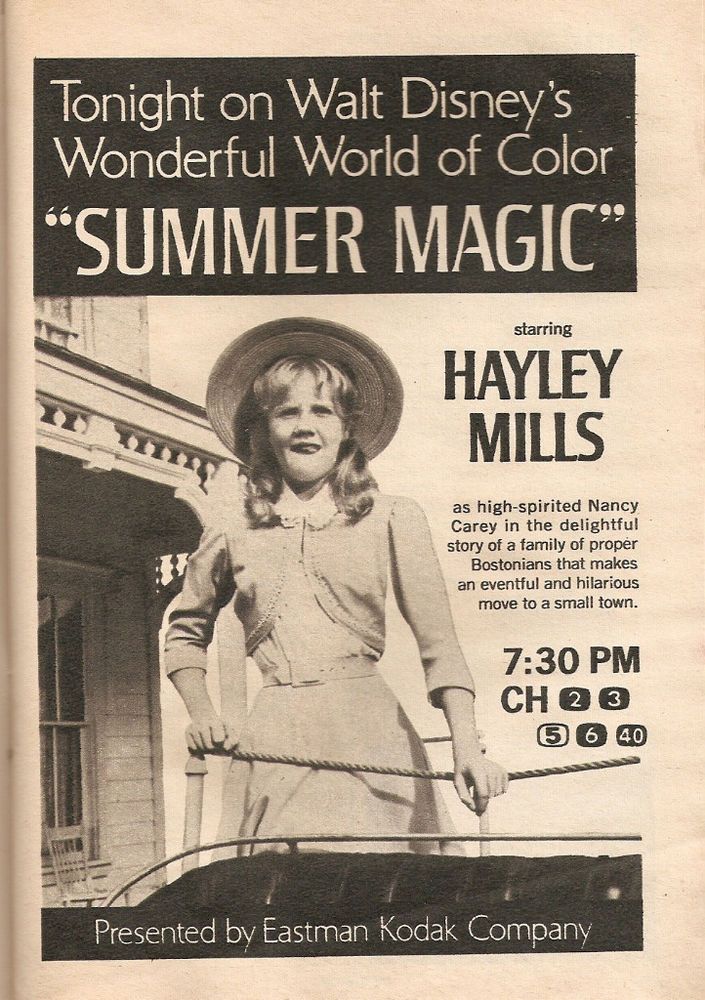

Summer

Magic (1963), the only Sherman brothers musical produced by Ron

Miller

Said the film critic for Variety of Walt Disney’s 1963 musical Summer Magic, “[t]he Disney trademark shows through all the way, meaning devotees of Tennessee Williams had better not be invited.” The remark was directed at a Hayley Mills movie with Sherman brothers songs, one of which involved Burl Ives, who five years earlier had been Big Daddy in M-G-M’s film of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, singing about an event known as “The Ugly Bug Ball.” Both of those films were about wealthy families in various states of decline; one in the South, the other in the North. The film’s co-producer, Ron Miller, was an ex-football player like Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’s Brick was, and within less than 20 years of Walt’s death, the studio had taken on a Williamsesque air like a stately old Southern mansion that had seen better days though the land it was built on was as solid as ever. And Miller took more of the blame for this than he deserved. While the company thrived without him, many of the things that helped it get back on its feet financially were things that got started when Miller ran the company.

Born April 17, 1933 in Los Angeles to middle-class Canadian parents, Ronald William Miller met and married Diane Marie Disney on May 9, 1954 at an Episcopal church in Santa Barbara while playing football at USC. Upon completing his service in the US Army, Miller joined the Los Angeles Rams. His athletic career lasted a mere two seasons before fate stepped in and saw him through to a different career path. After being injured in a game Walt Disney attended, Walt feared for his life and offered him a job in the company; he gladly accepted.

Walt

Disney celebrates the newlywed couple (source: The Walt Disney Family

Museum)

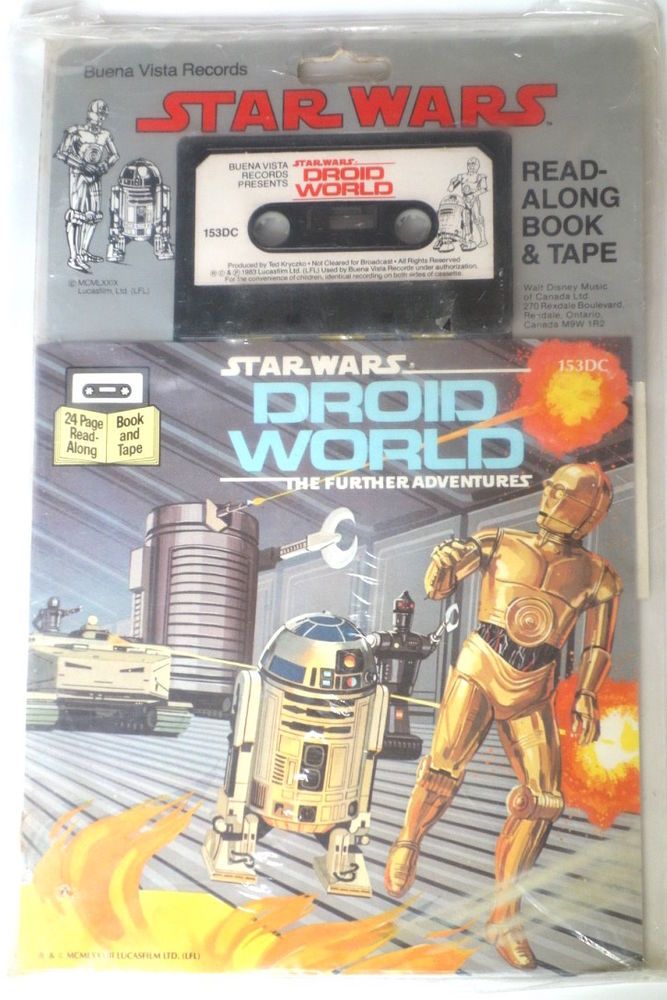

Over the next three decades, Miller went from a liaison between Walt Disney Productions and WED Enterprises during the construction of Disneyland to second assistant on Old Yeller to producer of the 1968 Dick Van Dyke comedy caper Never a Dull Moment to head of the company. After his eventual exile from Walt Disney Productions, he retreated to the Silverado Vineyards in Napa Valley. As the company grew exponentially under Michael Eisner, the official historical narrative tended to blame Miller for the company largely missing out on the cultural zeitgeist of the 1970s, the decade that gave us polyester leisure suits, pet rocks, and mood rings. As someone who missed all that by being born in the 1980s, time after time, all I ever heard about is how they missed out on Star Wars because of their overbearing ways along with slams at the studios’ movies of the era out of proportion to their actual flaws and with limited sense of context or understanding of how they got that way. But fear of missing out is manufactured fear, uncertainty and doubt, and now that they have finally gotten Star Wars for themselves, one can only come to the conclusion the company was better off cheering them on from the sidelines while going off in its own directions. Except that they did manage to score one aspect of Star Wars merchandising rights when it was new release: the audio storybook rights, as Buena Vista Records issued several of them.

Because of his background of having played football for the LA Rams for two years before Walt brought him into the company, background that no doubt helped in making a movie such as 1976’s Gus possible, people treated Miller as either a stereotypical “dumb jock” who married his way into the company as Diane Disney’s husband or as an out-of-touch fuddy-duddy content to live in the past. Neither characterization is accurate or fair. It is difficult to blame a single person for why they had more commercial flops than hits during this time period when so many decisions seemed to have been made by committee. The mere fact that they had such a committee at all makes it hard to blame any single person for every bad decision over a certain time period. Miller did not have absolute power. When he was head of the film division, he answered to E. Cardon Walker, COO since 1968, who took over as President after Roy O. Disney’s death in 1971 and with the full approval of the Disney family.

A company man through and through with a personality so strong one ex-Disneyite called him a “bully,” and whom Roy O. Disney (Walt's brother) had once unsuccessfully tried to fire, Walker worked his way up through the company’s ranks starting in the mail room in the 1930s. By 1960, he was on the board of directors. By 1976, he was CEO. He overpowered not only Miller, but Donn Tatum, the company’s prior CEO and its chairman until 1980. Most dangerously of all, he alienated Roy E. Disney, who resigned from the Presidency of the company on March 4, 1977, the year The Rescuers, Pete’s Dragon, The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, and Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo were the studio’s most prominent releases, believing the company’s magic touch was diminished without Walt around to guide them. When the younger Roy suggested moving beyond G-rated gimmick pictures, Walker accused him of wanting to make pornography. Roy disagreed and explained he merely wanted to make movies that were less formulaic. Walker felt that changing the established formula, which resulted in works ranging from minor hits such as Escape to Witch Mountain and The Apple Dumpling Gang to outright duds such as Superdad, was an affront to Walt’s memory. But Ron Miller was less resistant to change, up to a point. After all, Walt changed with the times, too, and the studio was doing things at the time of his death that were considered next to impossible in 1923 when the Disney brothers first incorporated Walt Disney Productions. The next seven years saw the first attempts at modernization since Walt died.

To

be fair to Roy, a lot of people underestimated his abilities at the time

at what ultimately proved to be their own risk. Even Walt didn’t believe

he’d amount to much. And his rivalry with Ron was similar in many ways

to the rivalry between Walt and Roy. But for now, Ron was in charge, and

the keys to the kingdom were in his hands. As Disney expanded into the

New York theatre scene with the Radio City Music Hall production of Snow

White Live —

another innovation wrongly credited to Miller's successors — and

its long-lost taped HBO special, it was time for the company to make the

first moves out of the Glass Coffin and into the harsh, unforgiving

light of the present day.

Take Down (1979), The Black Hole (1979), and Midnight Madness (1980): Three ways Disney thought outside of the G-rated box.

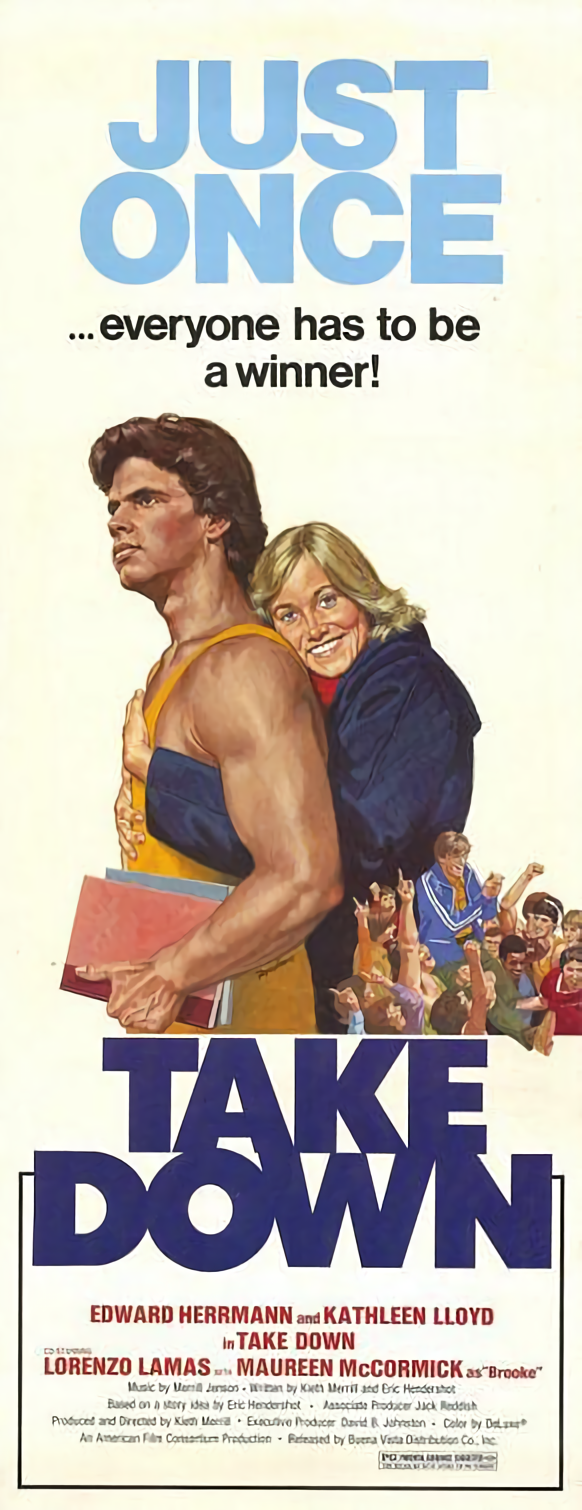

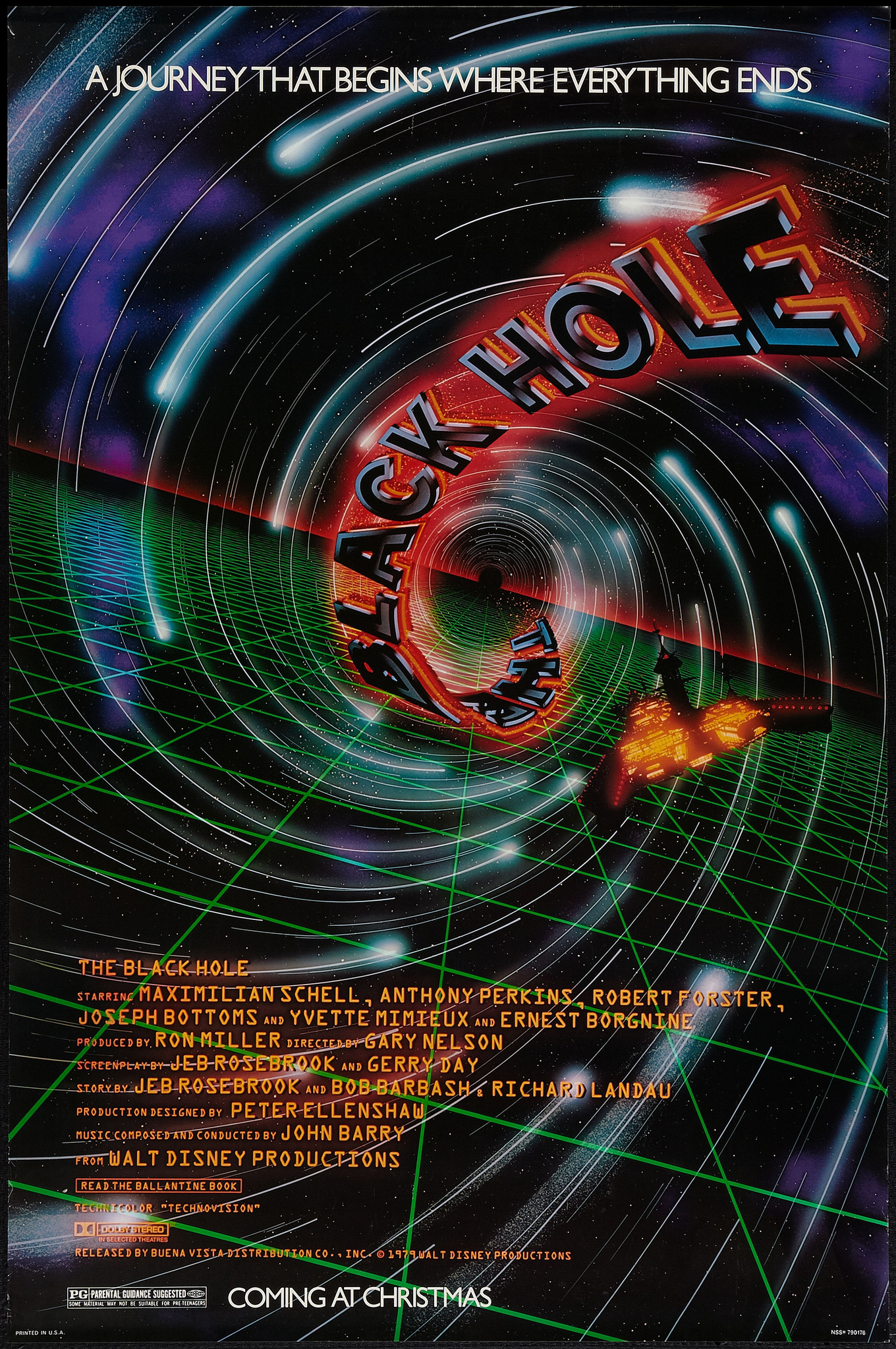

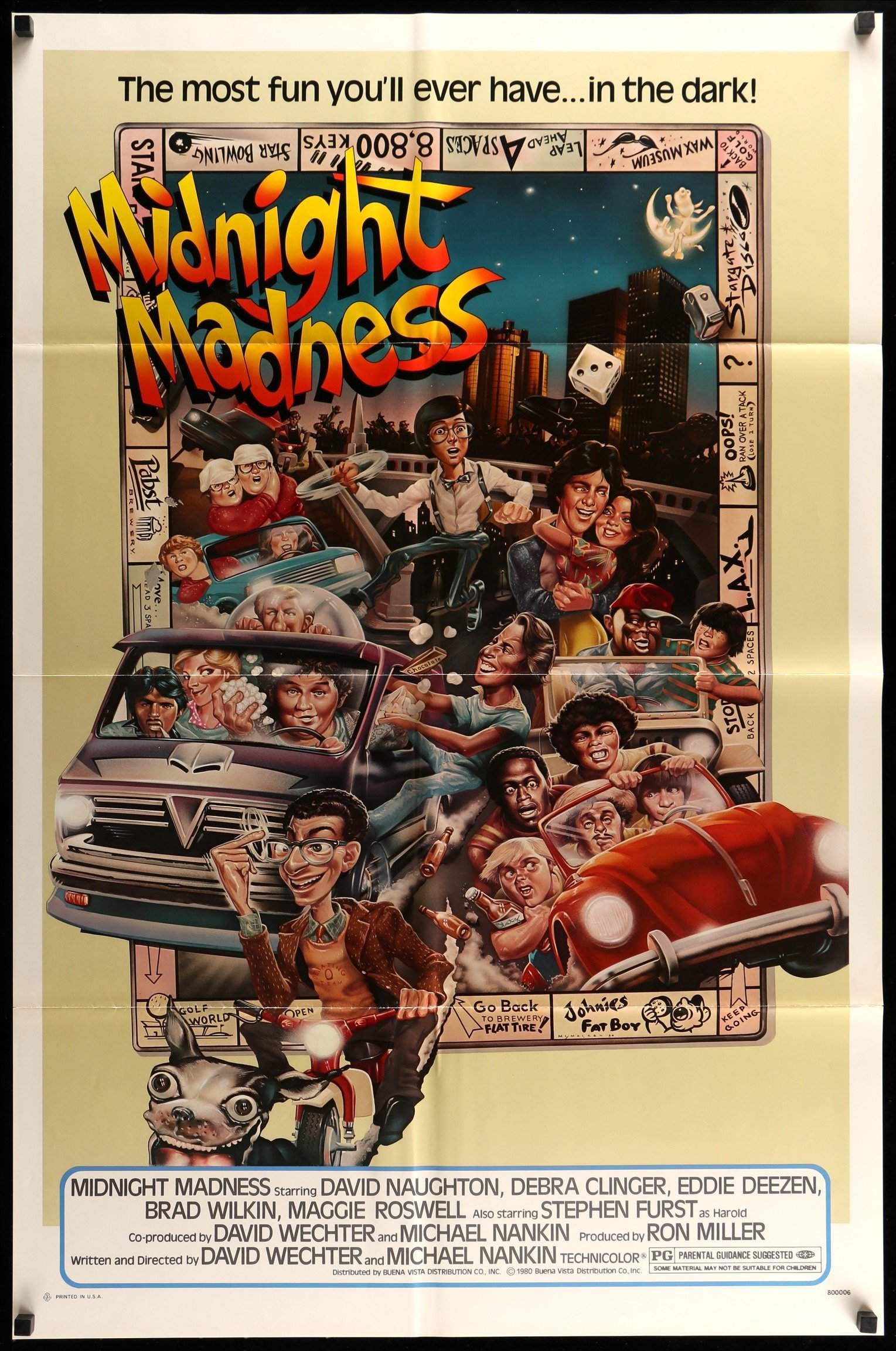

With the hopes of challenging the idea that Disney films were just for kids, the first thing to go was the ban on any movie rated anything higher than G. As Miller ascended to an executive position that covered the whole company and not just the film division, Tom Wilhite took his place as studio head with the promise that things were going to change drastically. Take Down (a Buena Vista acquisition from an independent producer), The Black Hole, and Midnight Madness were not box-office hits, but they showed that the studio was willing to try new things in drama, science fiction and comedy.

Filmed in Utah, Take Down starred Edward Herrmann as an English teacher who has to coach high school wrestling, a team whose teammates included Lorenzo Lamas. Also starring in the film were Maureen McCormick and Stephen Furst. While Buena Vista had made acquisitions of independent and foreign films in the late 1950s and the 1960s, they had stopped for awhile. This was their first in a decade, but one they quickly relinquished the rights to so someone else could release it on video. Though mostly forgotten today, it was still an important first step in this direction.

Disney's 1980 slate was partially disrupted when preview audiences laughed at unfinished effects in The Watcher in the Woods, which was supposed to be the third in a line of Disney-produced PG-rated movies. This pushed back its release by a year and prompted the studio to cut the film heavily in post-production, cuts the studio still refuses to restore to this day.

The first PG-rated film Disney actually produced itself, The Black Hole is often mischaracterized as a cash-grab attempt to copy Star Wars, when in truth it bears more of a resemblance to 20000 Leagues Under the Sea. Initially titled Space Station One, it had been in development throughout the 1970s under producer Winston Hibler, who died in 1976, forcing Miller to step in and replace him. Outside of being in space, the main difference between this and its more esteemed Walt-era predecessor is that there are women on the Cygnus. There were none on the Nautilus. The film wasn’t a total failure but it fell short of the box office bonanza they hoped for based on the larger-than-average publicity campaign that included network and syndicated TV specials, toys, books, lunchboxes and tie-in records. The film’s director, Gary Nelson, had directed the original 1976 version of Freaky Friday, one of the studio’s most successful films of the decade.

A mildly ribald college comedy built around problem-solving based on esoteric clues instead of monkey capers and blurring the line between science and magic like the earlier Merlin Jones and Dexter Reilly pictures, Midnight Madness was also an experiment in trying to see whether they could sell more tickets to teenagers and young adults without the Disney name attached to it. However, it outed itself as a Disney film in many ways: it features Mickey Mouse’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and many of the same personnel who had worked on past Disney live-action features were also credited in it. They might as well have kept the Disney name and taken their lumps because it might have grossed more than the paltry $2 million it made when it came out, although it became a minor cult favorite through HBO reruns and a here-today-gone-tomorrow home video release in the mid-1980s. After letting Anchor Bay have the DVD rights in the late 1990s, Disney finally claimed the film as its own when they re-released it on DVD in 2004 in that same old transfer from the original video release but with the (anachronistic for anything pre-1983) phrase “Walt Disney Pictures Presents” on the front cover; now, it has a spiffy new 1080p HD transfer on iTunes.

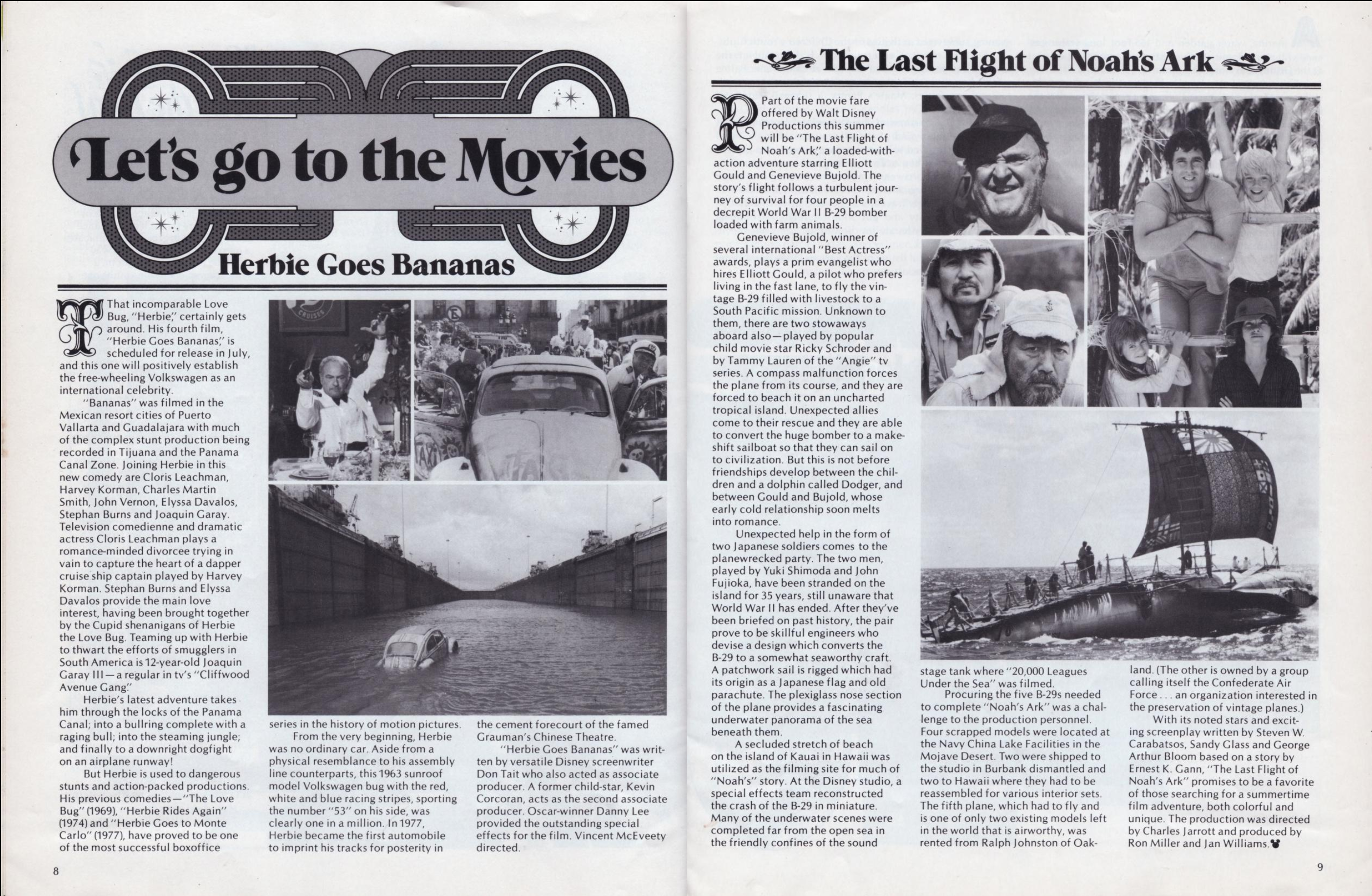

Disney kept making G-rated movies while venturing into the murky waters beyond that; based on the Daniel P. Mannix novel, The Fox and the Hound, despite being pushed back from Christmas 1980 to June 1981 by the Bluth Walkout, proved more successful than Herbie Goes Bananas or The Last Flight of Noah's Ark. Meanwhile, the PG-rated and Disney-branded Devil and Max Devlin (also pushed back from Christmas 1980 to February 1981) could not even outgross a reissue of Song of the South!

The

studio didn’t abandon G-rated movies altogether, and their experiments

showed that that alone was not the primary cause of box office success

or failure. The box office success of 1979’s G-rated The Muppet

Movie, which Disney now owns, proved that. The studio’s 1981

animated feature The Fox and the Hound, despite its relatively

dark subject matter and tone, got that rating and was far from a flop,

though its production saw an exodus among 13 members of the animation

staff who joined Don Bluth at his new studio. But the two live-action

films the studio made with Elliott Gould around this time were textbook

examples of this dual mentality. The first was The Last Flight of

Noah’s Ark, a G-rated 1980 release which paired him with

Genevieve Bujold, Ricky Schroder, and a giant airplane full of

livestock, while the second was The Devil and Max Devlin, a

PG-rated 1981 release in which Gould played a not-so-dearly departed

slumlord who needs to recruit three replacement souls to get out of a

Hell where Bill Cosby is the devil. Neither was a hit, but the PG-rated

film was the higher-grossing of the two despite protests from longtime

supporters of the company who objected to the mild profanity that was no

worse than anything allowed on network TV at the time. In hindsight,

it’s hard to argue Cosby was miscast, and the film seems like a classic

next to Leonard Part 6 and Ghost Dad, winning

the approval of Gene Siskel but not Roger Ebert. At the time, The

Cosby Show had not yet begun and he was known by the younger

members of the audience for Fat Albert and The Electric

Company while their parents likely remembered I Spy.

And then there was Condorman. Critics, a group of people whom Walt Disney distrusted, paid little mind to it, but since the film's release, the population of California condors has increased from barely even 20 to over 500, moving them from near-extinction to merely being critically endangered. They have even been reintroduced into the wild.

There were still limitations to how far they would go, though. Ron Miller told reporters, “the day we make an R-rated movie is the day I leave this company.” While they have made many since then, the bigger question is how many of them have stood the test of time.

1980

and 1981 also saw Disney collaborating with another movie studio for the

first time. Robert Altman's Popeye and Matthew Robbins' Dragonslayer

were the end results of a two-picture co-production deal with Paramount.

Michael Eisner was the head of the studio at the time, and they were

having the kind of immediate box-office success Disney hoped for. While

Paramount distributed these films in North America, Disney still managed

to pocket whatever profits they made anywhere else. Meanwhile, they

struck out on their own when The Watcher in the Woods, a

supernatural thriller starring Bette Davis, was pushed back from its

originally intended release date by a year when the climactic special

effects weren't ready yet. Meanwhile, about a reel of footage was cut

and the ending was changed. Future corporate administrations stood in

the way of attempts to restore the original cut after they agreed to

restore Bedknobs and Broomsticks and The

Happiest Millionaire to completion.

The next year saw the studio taking a bold new move with TRON. Wall Street investors found themselves baffled by the film, and Disney’s stock price dropped four points the day of its release. But it had its defenders, most notably future Disney employee Roger Ebert, who said:

“This is all a whole lot of fun. "Tron" has been conceived and written with a knowledge of computers that it mercifully assumes the audience shares. That doesn't mean we do share it, but that we're bright enough to pick it up, and don't have to sit through long, boring explanations of it.

There is one additional observation I have to make about "Tron," and I don't really want it to sound like a criticism: This is an almost wholly technological movie. Although it's populated by actors who are engaging (Bridges, Cindy Morgan) or sinister (Warner), it is not really a movie about human nature. Like "Star Wars" or "The Empire Strikes Back," but much more so, this movie is a machine to dazzle and delight us. It is not a human-interest adventure in any generally accepted way. That's all right, of course. It's brilliant at what it does, and in a technical way maybe it's breaking ground for a generation of movies in which computer-generated universes will be the background for mind-generated stories about emotion-generated personalities. All things are possible.”

TRON came in 22nd place for the year at the box office, though it still outgrossed all other Disney releases that year, new or old. At the time, however, it was still not enough to save Tom Wilhite's position within the company; he left to form Hyperion Pictures, which would go on to make The Brave Little Toaster when Disney passed on the rights to the book by Thomas M. Disch. But the audience’s knowledge of computers grew over time, as did their use in subsequent films, and TRON’s reputation grew along with it. Outside of that were Tex and Night Crossing, two more earnest, well-cast PG-rated dramas that got lost in the shuffle of a very competitive year in Hollywood. The former was based on an S.E. Hinton novel, and the latter was based on an actual story about a family trying to escape East Germany for West Germany in a hot air balloon. When Ron Miller became President of Walt Disney Productions, Richard Berger replaced Tom Wilhite as head of the studio. Miller offered the job to Michael Eisner, but he wanted the whole kit and caboodle, including the theme parks. Even though Eisner ultimately got what he wanted, perhaps Miller was right all along to sense that his skill sets were best kept with the film division.

The approach had not produced any major blockbusters yet, but it is still understandable why they would have wanted to go in that direction in the first place. Many of the cultural changes of the late 1960s and 1970s were regarding things Disney didn’t want to deal with, namely explicit sex and drug abuse. Their direct competition in the earliest part of the 1970s wasn’t Last Tango in Paris or Pink Flamingos, it was Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and Benji. And eventually, the venerable Wonderful World of Disney would have 60 Minutes to contend with. Right or wrong, the popular perception was that Disney was for children. They had no interest in showing exactly where babies come from; the closest they got to that was The Story of Menstruation in the 1940s. In an era where “do your own thing” was the mantra and nostalgia for the past was in, Disney was doing their own thing. They’d never stopped doing it. They felt little need to change until it became a matter of financial urgency. Not all the factors that threatened the company’s future were of their own making. The hyperinflation of the era that pushed movie ticket prices, theme park ticket prices, movie budgets, and the cost of new rides up along with everything else was not their fault. Another was the fact that the end of the Baby Boom and the subsequent decline in new births led to a greater median age and a decline in the number of children under the age of 14. Fewer children meant fewer new customers for Disney movies. It is also likely that the nationwide legalization of abortion thanks to Roe v. Wade played some part in this state of affairs.

Under

Ron Miller’s watch, the company was willing to venture beyond media that

existed when Walt was alive when they expanded into home video and cable

TV. While they licensed a few titles to MCA Discovision in 1978, their

first in-house releases on videotape and disc came in 1980. Walt Disney

Home Video provided the first opportunity to own copies of many of those

same cartoons, movies, and TV shows almost as if they were books. But

The Disney Channel also offered new TV shows and movies and even

acquired other studios’ content to fill time. Since Walt had embraced

television with open arms when it was a new technology even when other

studios feared it would doom them to oblivion, there was no doubt that

these were things Walt would have done as well, overriding a few

naysayers who wanted to keep things going as they always had been.

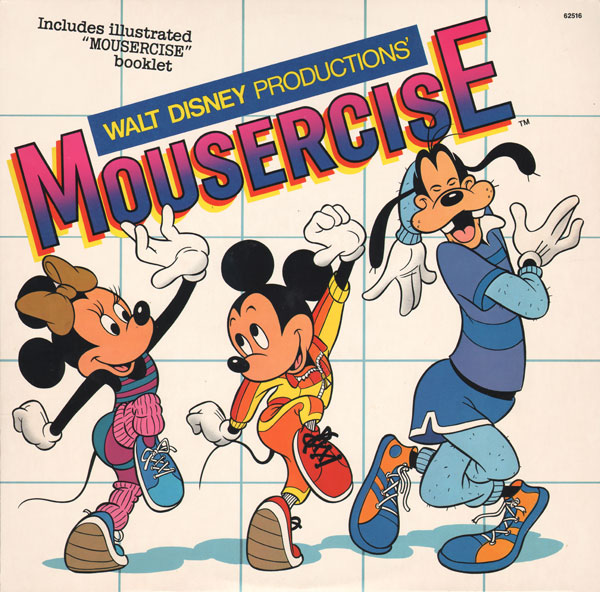

Originally intended as a partnership with Westinghouse Broadcasting, The Disney Channel provided the perfect platform for classic Disney movies, cartoons, and TV shows. Conceived as far back as 1977, eventually it grew to include original programming such as Welcome to Pooh Corner, Mousercise, You and Me Kid, EPCOT Magazine, Big Bands at Disneyland, and Canadian shows such as The Edison Twins and Danger Bay. The first Disney Channel sitcom wasn’t even a Disney production: Still the Beaver, Universal’s original cast reboot of the classic 1950s sitcom Leave it to Beaver, began production when Miller was still in charge of the company. Despite the success of the 1983 CBS-TV reunion movie, none of the big three networks wanted an old-fashioned family sitcom. None, that is, except for The Disney Channel. It didn’t air until November 1984 until Eisner had replaced him, but the new management allowed Ted Turner to swoop in and acquire the rights to the remaining seasons of the show and move it to WTBS to air along with the original series.

1982 saw great changes at the parks. While not exactly as Walt had originally intended it, EPCOT Center opened in Florida while the introduction of the full-day pass replaced the old E-Ticket system. 1983 saw the end results of the wise decision to make a licensing deal with the Oriental Land Company. What they got was Tokyo Disneyland, which has become one of the world’s most popular theme parks. So once again, the Ron Miller era gave us the first non-US Disney theme park. Meanwhile, back at Disneyland, New Fantasyland provided much-needed technological upgrades for a lot of the core rides of that particular land.

Unfortunately, despite such attempts to bring the park into the 1980s, a dark shadow hung over the parks in the form of a discrimination lawsuit against the company filed by two gay men ejected from Disneyland for “homosexual fast dancing” in 1980. While the ultimately company lost the lawsuit in 1984 (and lost another similar lawsuit against Walt Disney World in 1987), they had already relented in allowing a gay and lesbian group called The Tavern Guild to organize an event there on May 25, 1978 because they were not willing to risk a discrimination lawsuit. Accounts of the event vary from person to person like many events throughout LGB history, but the fact that these were not merely gay rights activist groups but an association of bar owners did not sit well with the company. There were still rules and regulations on the event: for instance, women could wear pants (after Freaky Friday and Pete’s Dragon such a restriction would seem hypocritical) but men could not wear dresses. Drugs and alcohol were forbidden just as they always had been. The irony of all this is that Ron Miller himself, in addition to later owning a winery, had been part of the push to remove restrictions against Jews at the Beverly Hills Country Club. He also let a transsexual, Wendy Carlos (née Walter), write the music score to TRON. But despite having gotten into the company through Disneyland, his input in the parks was minimal until he became head of the company proper.

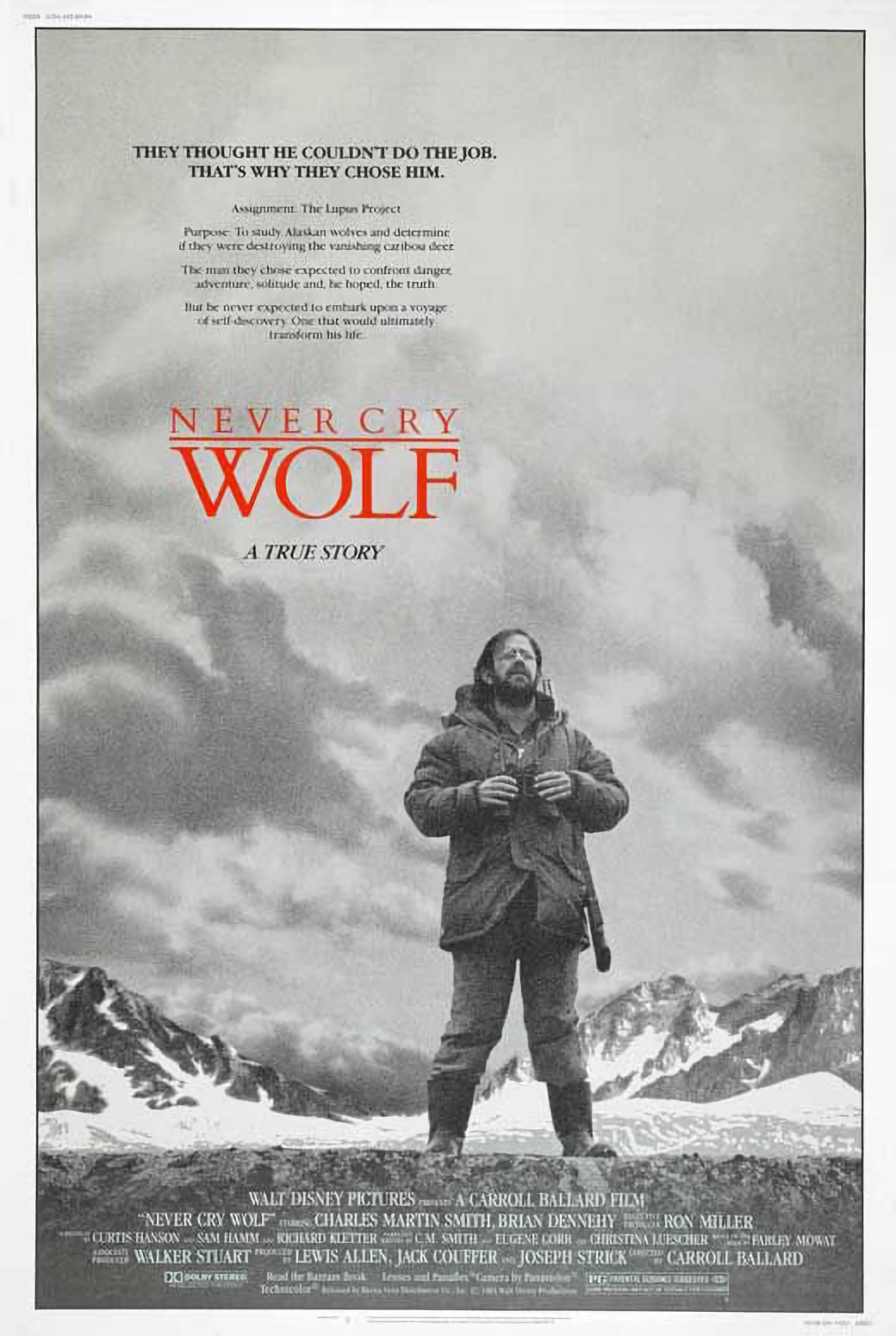

The

two major Disney theatrical film releases of 1983 showed how far outside

of the box Miller was willing to think in terms of what a Disney film

could be. While Jack Clayton’s Something Wicked This Way Comes

struggled at the box office after a troubled production despite moments

of genuine darkness and terror, Carroll Ballard’s Never Cry Wolf, shot

on location in Canada over a two-year period, eventually became a

success thanks to word of mouth. A starkly realistic drama about how

easy it is to upset the delicate relationship between human and nature,

the film was based on the 1963 memoirs of Canadian naturalist Farley

Mowat, here played by Charles Martin Smith in a far cry from his earlier

role for the studio in Herbie Goes Bananas. In a first for

Disney, it featured a brief glimpse of full-frontal male nudity, albeit

not enough to warrant any rating more severe than PG. The studio also

tried releasing another movie without the Disney name: Trenchcoat,

a murder mystery set and shot in Malta that starred Margot Kidder and

Robert Hays. Though the film was not a hit, its screenwriters, Jeffrey

Price and Peter S. Seaman, later wrote the screenplay to Who Framed

Roger Rabbit.

In a lighter vein, but one that showed he still showed a sense of reverence for the studio’s history, Miller also brought Winnie the Pooh and Mickey Mouse back to theaters in a pair of 25-minute featurettes. Not counting the compilation feature of his first three animated adventures, Pooh had only been gone from theaters for nine years, his return coinciding with the premiere of the live-action Welcome to Pooh Corner on The Disney Channel. Meanwhile, it had been a full three decades (and two Mickey Mouse Clubs, the second of which, the first to be racially integrated, had Miller as an executive producer) since the studio made a Mickey Mouse cartoon. Screen audiences were obviously happy to have him back; his return in Mickey’s Christmas Carol earned an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Short. It didn’t win, and neither have any of the Mouse’s subsequent silver screen outings to date, making him the Susan Lucci of cartoon mice. But it was his Dickensian turn here that made even Mickey cartoons possible, the most recent ones being the highly acclaimed Disney Channel short cartoons. It also helped make DuckTales, a major TV success over two generations, possible.

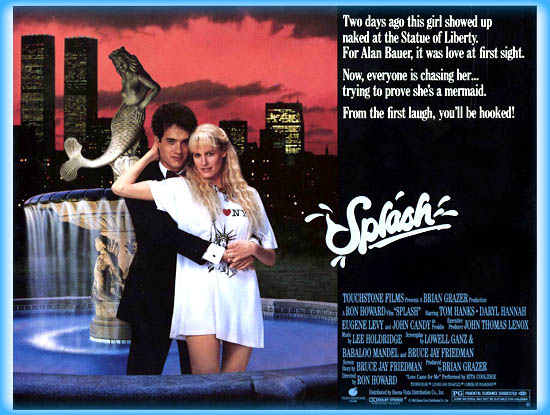

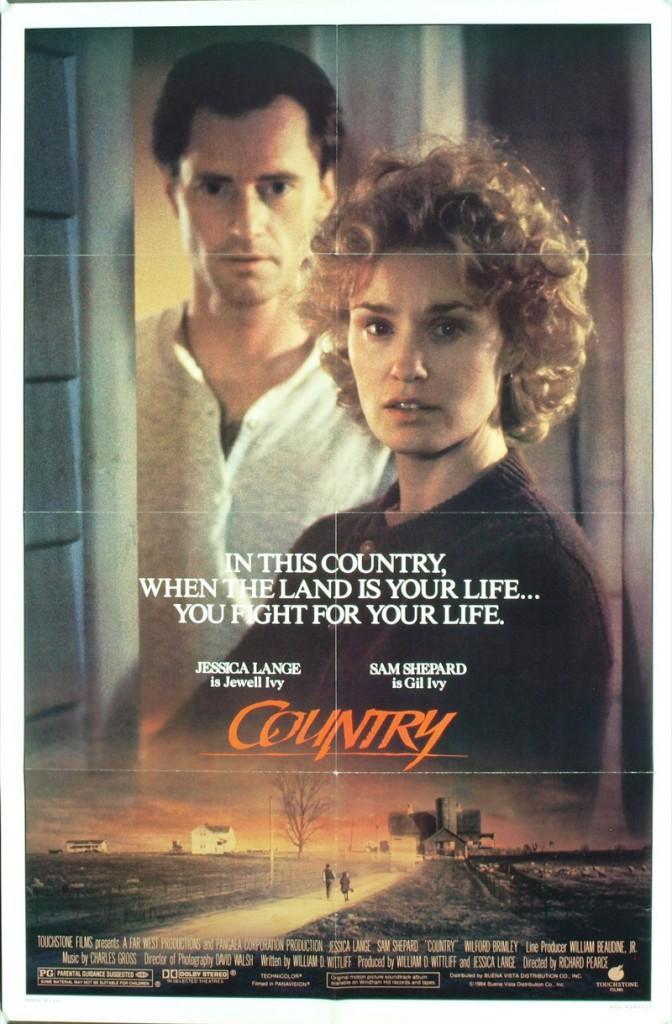

1984 should have been a very big year for the company. It was, just not in ways anyone expected. At first, things started off well; the first quarter of the year saw the first Touchstone Pictures release, the romantic comedy Splash with Tom Hanks and Darryl Hannah, and indeed it made as big a splash at the box office as any Disney film since the original Love Bug 15 years earlier. The second Touchstone release, a grim farm family drama called Country, would eventually earn an Oscar nomination for Jessica Lange. But the company’s board of directors got tired of waiting for things to turn around faster. Roy E. Disney resigned so there would be no conflict of interest when he staged a boardroom coup to force a change of management. Another threat to the company’s future came in the form of Saul Steinberg, who wanted to buy the company and break it up. He was ultimately unsuccessful in his goal, but the damage was done. Disney had to pay a huge sum of money in greenmail to make him go away, and that depleted the company’s finances.

With both his job and his marriage on the line, he chose to save his marriage instead. During a time when the last (to date) Herbie movie was their tentpole release, Ron and Diane had stopped speaking at the breakfast table. They even separated for awhile; while they were separated, he lived in John Wayne’s former house while he saw another woman. This cost him the support of board members, even Lillian Bounds Disney, Walt’s widow, whose second husband had recently died. Miller took the fall, resigned from the company in September and spent the remainder of his life on the Silverado winery in Napa Valley, which he had purchased a few years earlier. So you can be President of the United States and cheat on your wife, just not President of Walt Disney Productions, at least not as it existed then. They could take Walt Disney Productions away from him, but not the status of being the father of Walt Disney’s grandchildren.

The new management had little faith in the remaining Miller-era films in the pipeline. That was obvious when Jeffrey Katzenberg cut 12 minutes of finished animation from The Black Cauldron as if it were just another live-action film. This was largely unheard of at the time; in the pre-CGI days, the filmmakers usually excised deleted scenes before they got to the ink and paint stage. The film, a latecomer to home video that got no theatrical releases in the US outside a very short, re-branded 1990 reissue in a few select cities, has recently been released on Blu-ray, but those excised trims have yet to be located, leaving fans to wonder what might have been had the Ron Miller cut (or whatever you want to call it) actually been released.

A

glimpse of what might have been if The Black Cauldron had not

been severely cut by order of Disney's new management.

Based

primarily

on the second in the Chronicles of Prydain series of books by

Lloyd Alexander, The

Black Cauldron also tries to combine elements from the

other books without a lot of screen time to do so. That's a huge task to

ask of anyone, even the Disney animation staff, and the film gives them

less than 90 minutes to do so. But the actual production was so big and

so ambitious it got pushed back not once but twice: first from a Christmas

1980 release date to a December 1984 release date, and then from

that to a summer 1985 release date! Don Bluth's departure with more than

a dozen coworkers plus a couple of Animation Guild strikes also put more

pressure on the production team. By that time, the whole thing was out

of Miller's hands and into Katzenberg's, and his insistence on cutting

the darkest parts of the film and replacing it with hastily drawn

substitutes doomed the film.

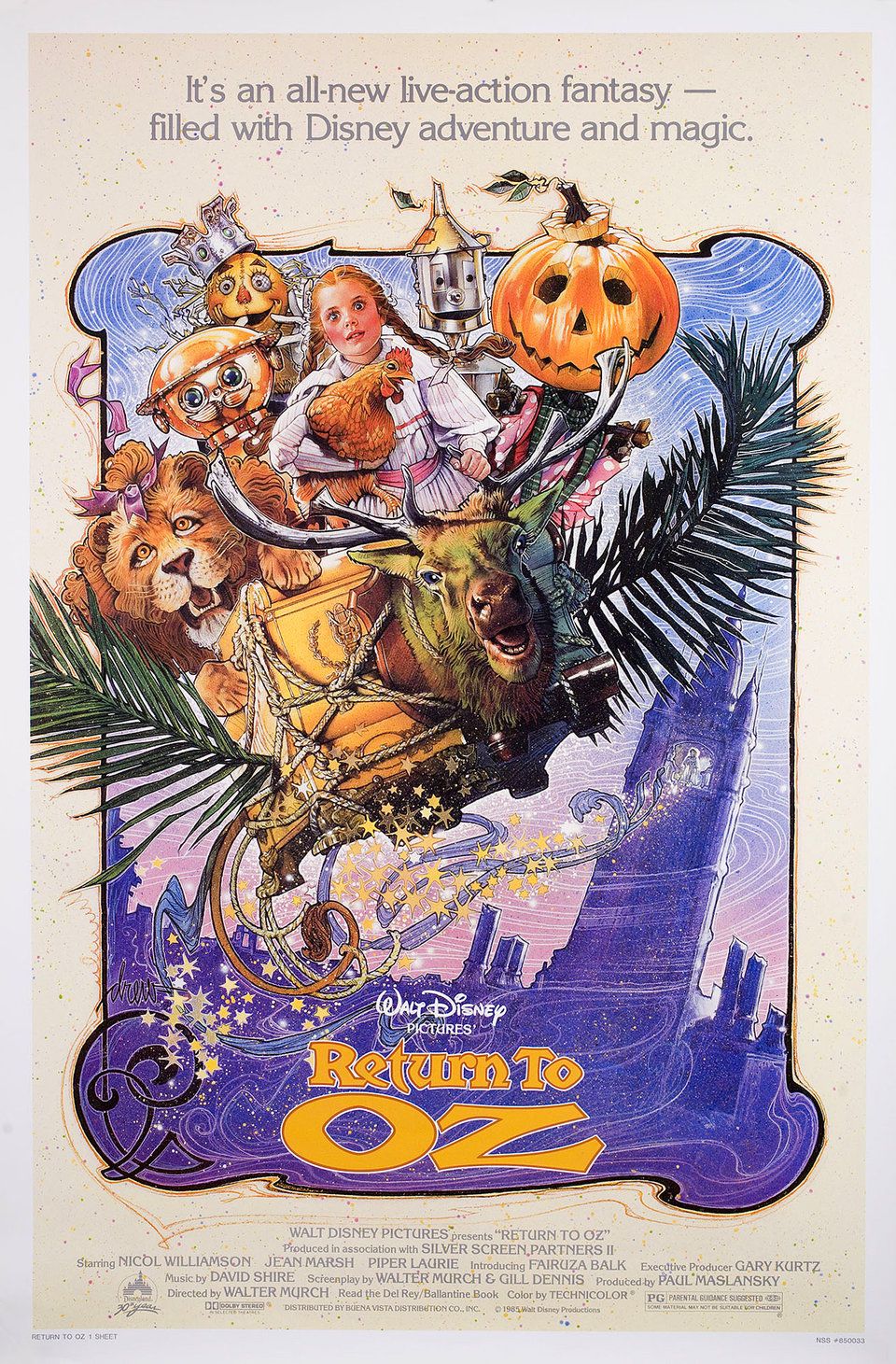

The new management also showed little faith in the remaining films that had gotten the greenlight under Miller: Country (despite Jessica Lange’s eventual Oscar nomination for it), Return to Oz, The Journey of Natty Gann, Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend, and My Science Project (unceremoniously dumped in theaters and overshadowed by Universal’s Weird Science, which opened one week earlier).

We're off to see … whoever is running Oz now that the Wizard's gone: the bright and cheerful artwork for 1985's Return to Oz gave no indication of the actual tone of the movie and also gave the impression the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly lion would have more time in the film than they did.

In

fact, it is the second of those films, Return to Oz, filmed in

England and co-written and directed by Walter Murch who also edited the

picture and sound for Apocalypse Now, that has the most to say

about the studio at that time. Combining the books Ozma of Oz

and The Land of Oz, Oz without the Wizard is the perfect

metaphor for Disney without Walt. The magic is still there, but it is

buried under cobwebs, rust, and varying states of decay and tyranny and

just needs Dorothy to come back to put everything in order. Despite a

haunting score by David Shire that evokes the feeling of both the

Romantic and Ragtime eras and an elegant visual style that paid tribute

to the original book illustrations by W.W. Denslow, the film didn’t

become a moneymaker. Neither did 1939’s The Wizard of Oz or

1978’s The Wiz, for that matter, but in this case Fairuza Balk’s

Dorothy is the closest in age to how L. Frank Baum originally conceived

her. Walt Disney Home Video did not help matters much when the box they

designed for the eventual release tried to look tonally less like the

film itself and more like that for the iconic M-G-M musical version that

had also been released on tape and was still shown on CBS every year.

Disney couldn’t ignore its influence entirely, as they still followed

the template of making Dorothy’s Kansas antagonists (Nicol Williamson

and Jean Marsh) into Oz villains, and they actually had to pay the

studio to use the ruby slippers. Even so, over 35 years have been

powerless to obscure this film’s virtues. In making the film at all, Ron

Miller succeeded where Walt failed at actually making a film about the

Land of Oz (Walt made Babes in Toyland instead and made Ray

Bolger the villain).

A glimmer of hope for the animators came when a movie that started under Miller but finished under Eisner proved more successful, despite the literalism of the title: The Great Mouse Detective. The next big hit in animation also mixed it with live-action footage: Who Framed Roger Rabbit, based on a Gary K. Wolf book Disney had acquired the rights to in 1981 and that they had started animation tests on no later than 1983, but they had to finish the projects they had already started first. Eventually, those two movies helped ensure that animation would still have a future at Disney. Once The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King became hits, those who had started under the “What Would Walt Do” years and stuck it out were richly rewarded by having earned the right to carry the torch of Disney animation. Sadly, that torch would start to flicker out yet again just as soon as it regained momentum. 10 years later, the medium that Walt Disney spent his whole life trying to perfect was no longer practiced by Disney except for a few isolated projects here and there.

Work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit began before Michael Eisner replaced Ron Miller as the head of Disney. At this point, Paul Reubens, who had a small role in Midnight Madness and would star in ex-Disney animator Tim Burton's directorial debut Pee-Wee's Big Adventure, was the character's voice.

The irony of Disney’s rapid regrowth is that by now, it has become the very same thing it used to be afraid of: a corporate raider. Back in the 1980s, they were afraid of being bought out. Now they’re the one doing the buying. First Miramax, then ABC, then Saban Entertainment, then the Muppets, then Marvel Comics, then Lucasfilm, then most recently 20th Century Fox. Ironically, this was part of Miller’s strategy to fight off Saul Steinberg. Buying out Gibson Greeting Cards and Arvida Corporation was what is known in the business world as the poison pill strategy, a common (and usually last-resort) tactic to make a company seem less attractive by taking on a huge amount of debt which the party proposing to buy it out would ultimately have to pay off if successful in taking it over. Prior to that point, they had been relatively debt-free. In this case, Miller’s victory against Steinberg was a pyrrhic one when it came to his career, but one that nonetheless preserved the company’s independence and made it possible for them to recover without being a subsidiary of some other company who might just as well break it all up at a moment’s notice. Disney sold the Arvida holdings three years later yet still expanded their real estate holdings in other directions in the 1990s by building the town of Celebration, Florida. That was intended to represent the parts of Walt’s dream that EPCOT the park did not include, but it still fell short of that ideal in some ways.

Ron died on February 9, 2019 at the age of 85. Without the Steinberg debacle, who knows how the rest of Disney’s history would play out and how much longer Miller would have stayed at the company. His 65th birthday was in 1998, which was also the 75th anniversary of the incorporation of what was now called The Walt Disney Company and had been since 1986. If he had stayed in football, that might have had a negative effect on the outcome of his health, considering how many former NFL players have died of dementia-related illnesses. Walt probably saved his life by hiring him. But when he left Disney, he left the film industry altogether. Betrayed by the lack of support from board members he thought he could count on, he turned down an opportunity to continue to be part of the company via an independent production deal.

Saul Steinberg (1939-2012) derailed Miller's plans for modernizing Disney by buying up the company's stock to force them to buy out his shares at an inflated sum to chase him away.

The company’s attitude towards him and his legacy evolved over time. They wouldn’t give him a Disney Legend award although they would give one to E. Cardon Walker and various individuals who worked at ABC prior to 1995! Never as big of a publicity hound as his predecessors, he nevertheless granted requests for an interview to Leslie Iwerks, daughter of Ub, for her documentary Walt: The Man Behind the Myth, which the company commissioned for the centennial celebration of Walt Disney’s birth. He also granted an interview to a Disneyland documentary that appeared on a Walt Disney Treasures DVD set. Since he never wrote a memoir, biographical information is largely dependent on two sources: Storming the Magic Kingdom by John Taylor (1987, Alfred A. Knopf) and DisneyWar by James B. Stewart (2005, Simon and Schuster). With the benefit of time having passed and the company being in crisis again for different reasons, Miller comes off looking better in the latter book.

During this same period, a young woman named Lora Mumford, who has since passed away, auditioned for a sci-fi rock band at Disneyland called Halyx. When Elektra Asylum Records dropped their plans to release an album for the band (and subsequently misplaced the master tapes), Disney’s record label, who felt they were ill-equipped to handle anything edgier than Mickey Mouse Disco, signed Mumford to some children’s pop records. One notable track was called “You Can Always Be Number One” where she sang this refrain:

Goofy has been known to goof,

That’s how he got his name

But G-O-O-F-Y

He never quits a game;

He jumps right up and plays again

When you think he’s through.

If he can do that every time,

Think what you can do!

This sums up the company under Miller as well as anything. Disney had fallen down and gotten back up more times than Hollywood and Wall Street could count, but they came out of it stronger than ever before. Miller became the scapegoat for the company’s Great Recession-era struggles, and someone else got the credit for capitalizing on things that had started when he was still at the company, but he still landed on his feet, and even the biggest flops greenlit while he was there still demonstrated more willingness to try new things than the studio had been in quite a long time, and they were still rooted in the belief that the Disney way was one worth carrying on through the generations. Although he and Don Bluth never patched things up, the company tried to let bygones be bygones with each of them individually. A few years before he died, Miller came back to Disneyland for the very first time since the 1980s for its 60th anniversary. He was also actively involved with the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco, California. That’s where I met him and his daughter Joanne, a moment I consider one of the best experiences of my life. I didn’t get to meet any of the other members of the family when my mother and I went to the Silverado Vineyards in Yountville, CA. Looking at the place, you would hardly find anything there that indicates that it is owned by the Disney family. In fact, the only thing there that outs it as having anything to do with Disney at all is a poster for Ratatouille, a film where the family of a late, great French chef allows his name to be bastardized to sell TV dinners. Well-played, Ron.

And I have to say, they really sold me on the idea of a jalapeño wine.